Viral Recordings Force a Reckoning With Privacy in Modern Dating Culture

A fast moving scandal forced a confrontation with how visibility, monetization, and consent now collide in everyday life

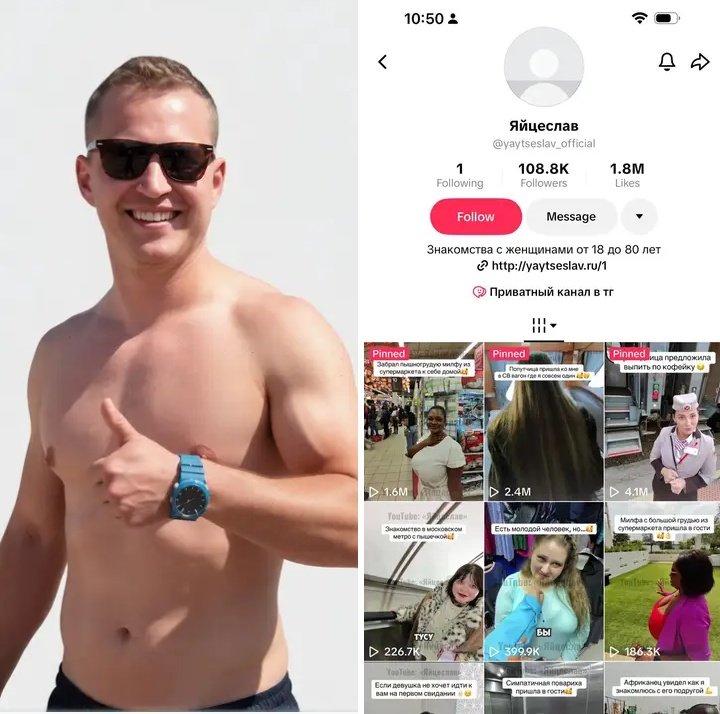

The story spread first through clips, then through argument. By the time officials reacted, the narrative had already hardened online. A man presenting himself as Russian, widely referred to as Yaytseslav, became the center of a controversy that moved from Accra to Nairobi and Mombasa within days. The pattern described by women and viewers was consistent enough to trigger outrage, yet fragmented enough to resist easy legal framing.

Public encounters filmed in malls, streets, or supermarkets appeared harmless at first glance. Compliments, phone numbers exchanged, quick familiarity. The discomfort emerged later, when short clips began circulating online and longer recordings surfaced behind paid channels. Allegations followed that some intimate encounters were recorded without clear consent and distributed for profit. By the end of the week, the controversy had stopped being about one individual and started revealing something broader about how intimacy, content, and money now intersect.

The speed of amplification mattered. Platforms rewarded curiosity before facts settled. Public reaction filled the gap left by slow institutional response, and debate turned messy. Some discussions focused on personal responsibility, others on exploitation. The deeper question sat underneath both arguments. What happens when private encounters become monetized media before law enforcement even understands the mechanism?

The Platform Economy Meets Private Life

The infrastructure behind the scandal was familiar. Short clips circulated on platforms such as TikTok and YouTube, while longer content reportedly sat behind subscriptions on Telegram, often priced at about $5 per month. The model mirrors a broader creator economy logic where attention converts directly into revenue.

What unsettled many observers was not only the sexual nature of the material but the apparent efficiency of the funnel. Public interaction became teaser content. Private interaction became paid content. The line between personal encounter and digital product blurred almost instantly.

This dynamic exposes a tension platforms have struggled with for years. Moderation systems respond to explicit violations once identified, yet the economic incentive sits upstream. Viral reach rewards boundary pushing long before enforcement begins. Content removal arrives late, often after downloads and redistribution have already occurred beyond platform control.

The result is a system where accountability fragments. Platforms point to user responsibility. Users point to platform design. Law enforcement arrives last, dealing with evidence that has already spread across jurisdictions.

Consent in the Age of Wearable Recording

Much of the anger surrounding the case rests on uncertainty rather than confirmed facts. Viewers do not know what conversations took place off camera. Participants may have consented to intimacy while not consenting to recording or distribution. That distinction sits at the center of modern image-based abuse cases.

Wearable recording technology complicates this further. Smart glasses and discreet cameras collapse the visible boundary between being filmed and not being filmed. Social norms have not caught up. Many people assume recording requires a visible device. Increasingly, that assumption is wrong.

The law tends to move slower than technology adoption. In Kenya, the Computer Misuse and Cybercrimes Act, 2018 criminalizes the wrongful distribution of intimate images, with penalties that can include fines up to KSh 200,000 or imprisonment for up to 2 years upon conviction. Enforcement, however, depends on complaints, evidence, and proof of lack of consent. Those thresholds are difficult when encounters occur privately and participants fear public exposure.

Consent itself becomes contested terrain. Agreement to meet is not agreement to record. Agreement to record is not agreement to publish. These distinctions sound obvious in theory. In practice, they become legally complex once content circulates across borders.

Ghana’s Response and Kenya’s Uneasy Silence

In Ghana, officials moved more visibly. The Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection condemned non-consensual recording and distribution, framing it as a violation of dignity and privacy. The Cyber Security Authority reportedly began examining the circulation of explicit material, alongside efforts to push for takedowns.

In Kenya, official response appeared indirect. The Directorate of Criminal Investigations issued a Valentine’s period advisory encouraging caution when meeting strangers, without naming the case. Public reaction filled the vacuum. Online commentary ranged from concern about digital exploitation to familiar cycles of blame directed at women involved.

The contrast reveals an institutional dilemma. Naming an individual prematurely risks legal exposure. Remaining silent allows online narratives to dominate. Either choice carries consequences, especially when social media frames the story before investigations mature.

Rumor, Fear, and the Absence of Verified Harm

As attention intensified, unrelated claims began attaching themselves to the story. Allegations involving disease transmission circulated widely despite the absence of confirmed medical reports or official health warnings. Similar rumors have followed other viral scandals, often reflecting public anxiety rather than evidence.

The pattern is predictable. Sexual controversy invites moral panic. Health fears amplify engagement. Facts struggle to compete with speculation once emotional momentum builds.

This environment complicates reporting and enforcement alike. Victims may hesitate to come forward if they fear becoming characters in an online spectacle. Authorities risk appearing reactive if they respond to rumors rather than verified complaints. The noise obscures the central issue, which remains consent and distribution rather than unproven health claims.

Cross-Border Problems Without Clear Jurisdiction

The case also illustrates how digital misconduct resists geographic boundaries. Encounters reportedly occurred in multiple countries. Content distribution took place online. Payment systems operated independently of local regulation. By the time public pressure mounted, the individual at the center of the controversy was believed to have left the region.

International cooperation exists through mechanisms such as Interpol, yet such processes require formal complaints and evidence thresholds that viral scandals rarely meet immediately. Without complainants willing to pursue cases across borders, enforcement becomes slow and uncertain.

Meanwhile, content continues to circulate. Deletion on one platform does not remove copies elsewhere. The digital footprint persists even when accounts disappear.

A Mirror Held Up to Dating Culture Online

The intensity of reaction reveals something beyond outrage at one person. Modern dating increasingly operates through speed and proximity. Messaging apps compress timelines. Meeting strangers has become routine, especially in large urban centers. The expectation of privacy remains rooted in older assumptions, even as recording technology and monetization models evolve.

The discomfort many people expressed online came from recognition. The scenario felt familiar. The outcome did not.

There is also an uncomfortable gender dimension. Public debate often drifted toward judging women’s decisions rather than examining the economics of recording and distribution. That reflex says as much about social attitudes as it does about the scandal itself. Responsibility becomes easier to assign to individuals than to systems that reward exposure.

Where the Story Leaves Institutions

As of February 14, 2026, no confirmed arrest or formal charges have been publicly announced in connection with the case. That absence has fueled frustration, but it also reflects the difficulty of translating viral controversy into prosecutable evidence.

What remains is a pressure point. Governments across Africa are confronting a reality where digital abuse moves faster than legislation designed for earlier internet eras. Platforms face growing scrutiny over monetized intimate content. Users are learning, sometimes painfully, that privacy assumptions no longer hold.

The story may fade from timelines soon enough. The underlying conditions will not. Recording technology will become cheaper. Distribution channels will remain global. The next controversy will likely follow a similar path, unless legal standards and platform accountability evolve at the same pace as the tools themselves.

For now, the Yaytseslav scandal stands less as an isolated episode than as a moment that exposed how fragile personal boundaries become once intimacy enters the content economy.

Go to TECHTRENDSKE.co.ke for more tech and business news from the African continent and across the world.

Follow us on WhatsApp, Telegram, Twitter, and Facebook, or subscribe to our weekly newsletter to ensure you don’t miss out on any future updates. Send tips to editorial@techtrendsmedia.co.ke