The Green Economy Returns Agriculture to the Centre of Policy

Agritech enters agriculture with big expectations but finds a sector shaped by risk, distance, and systems that evolved long before digital tools arrived

Agriculture still carries the weight of Africa’s climate conversation, even when attention drifts elsewhere. At the Climate Tech & Investment Summit, the discussion returned to something less fashionable but harder to ignore. Farming remains the place where climate risk, finance, and livelihoods collide every season. Technology enters that space not as spectacle but as infrastructure.

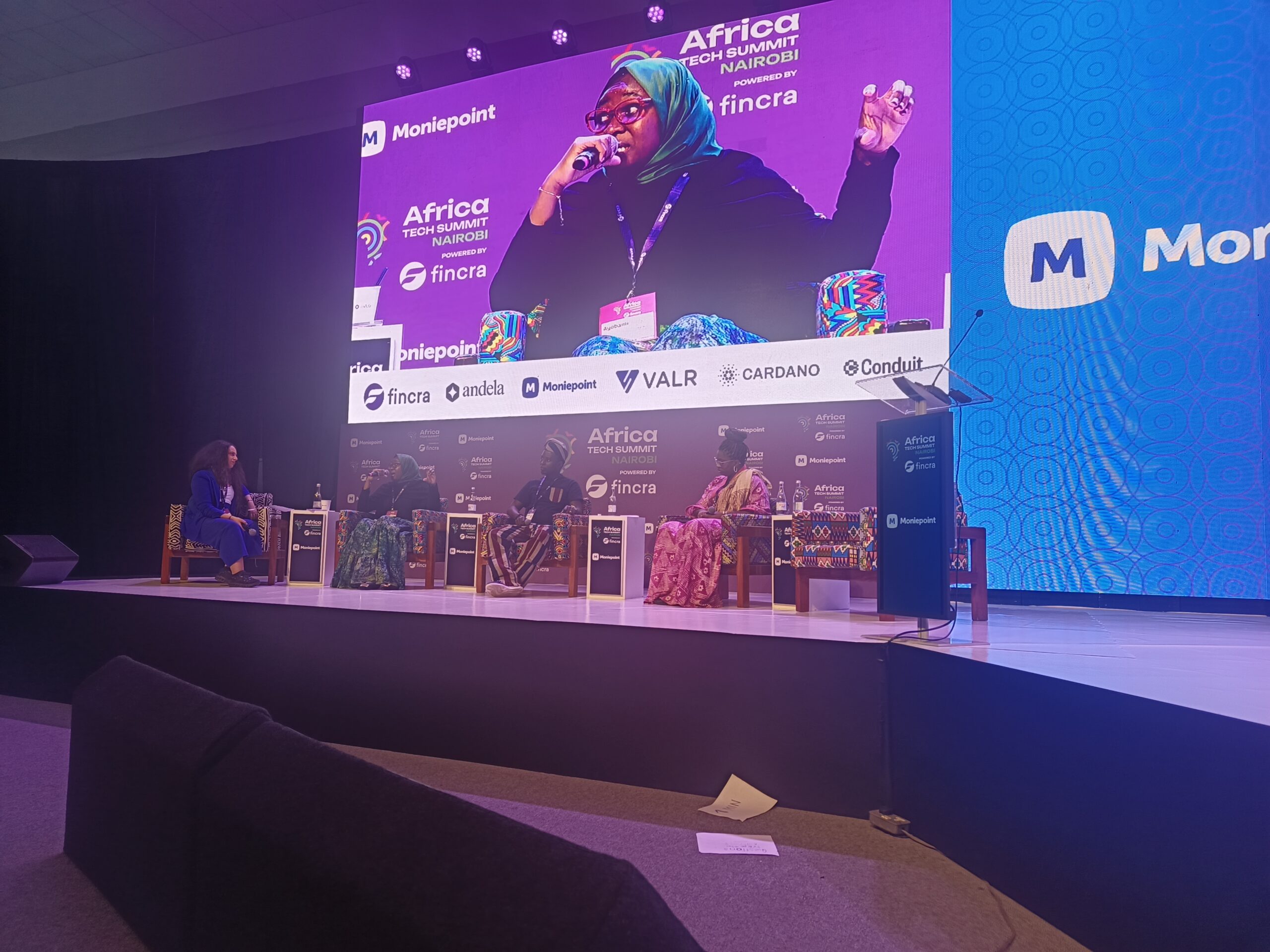

On the Moniepoint Stage, moderator Haifa Ben Salem of the International Trade Centre guided a conversation that stayed close to ground realities. Ayobami Oladipo of Ignitia spoke from the vantage point of weather intelligence. Babafemi Adewumi of Crop2Cash approached the sector through digital finance and farmer identity. Princess Ogbechie of Farmz2U focused on logistics, aggregation, and how existing rural systems actually function. Different entry points, same friction.

The green economy, in this framing, looks less like carbon accounting and more like risk management. Floods arrive earlier than expected. Dry spells stretch longer. Inputs become expensive at the wrong moment. Farmers absorb the volatility because someone has to. Technology attempts to redistribute that uncertainty across the chain.

That ambition sounds straightforward. Execution rarely is.

When Technology Meets the Limits of Infrastructure

One recurring observation sat beneath nearly every intervention. Most farmers operate in environments where connectivity remains inconsistent and smartphones are not the default device. The assumption that digitization begins with apps continues to run into physical limits. Network gaps, distance from banks, and literacy barriers remain stubborn facts.

Crop2Cash’s approach reflects this reality. The platform built around USSD and feature phones acknowledges that adoption follows familiarity. Farmers already understand simple mobile interactions. Extending financial services through those channels reduces friction in ways more sophisticated interfaces often fail to do. Over time, transaction history becomes a form of financial identity, which lenders can interpret as behaviour rather than guesswork.

Ignitia’s work arrives from a different angle but lands in the same place. Weather forecasting in tropical regions has long suffered from poor accuracy. Improving forecast precision is not an abstract technical exercise. It determines whether fertiliser is applied before rainfall or washed away hours later. It influences planting decisions and insurance calculations. When forecasts improve, uncertainty narrows. That narrowing carries economic consequences.

The discussion kept circling back to infrastructure. Not roads or storage alone, but informational infrastructure. Who knows what, and when.

Inclusion as a Design Constraint, Not a Moral Argument

Agriculture’s inclusion problem often gets framed as a social objective. In practice, it functions as a design constraint. Systems that exclude smallholder farmers simply fail to scale because smallholders dominate production across much of the continent.

Princess Ogbechie described an approach that begins with observation rather than replacement. Many farming communities already operate organized systems of aggregation and distribution. They move produce through trusted intermediaries. Attempts to digitize those relationships from outside often collapse because they ignore how trust already operates locally.

Instead, Farmz2U layered digital tools onto existing structures. Younger participants in farming communities, often more comfortable with internet tools, become intermediaries between digital platforms and older farmers. Adoption spreads unevenly but organically. The system absorbs technology rather than being forced into it.

There is an uncomfortable implication here. Some infrastructure problems remain outside the reach of startups. Banking access, connectivity, and transport networks still depend on public investment. Technology adapts around those gaps rather than solving them outright.

The Investment Question Lurking Behind Climate Language

Climate discussions frequently circle around sustainability language. Investors tend to ask a different question. Can risk be measured well enough to justify capital?

Agriculture has long struggled on that front. Weather volatility, fragmented land ownership, and weak data trails make lending difficult. Agritech firms increasingly position themselves as translators between farmers and finance. Data from transactions, weather models, and production cycles begins to replace assumptions.

That process carries tension. Better data can attract capital, but it also introduces new expectations around performance and repayment. Farmers gain access while absorbing new forms of accountability. The balance between inclusion and financialization remains unsettled.

Government involvement surfaced repeatedly during the session. Public programmes still reach farmers at scale in ways private platforms cannot. Collaboration between state institutions and agritech firms remains uneven, sometimes slowed by bureaucracy, sometimes by mistrust. Yet without that coordination, many initiatives stall before reaching meaningful coverage.

Collaboration as Survival Logic

Competition rhetoric sits awkwardly in agriculture. The value chain is too interdependent. Weather services require distribution networks. Financial services require reliable production data. Aggregators rely on both. Each layer depends on the others functioning reasonably well.

Several speakers described collaboration less as strategy and more as necessity. The sector’s fragmentation makes duplication costly. Efforts that operate in isolation tend to exhaust resources without resolving underlying constraints.

There is also a cultural dimension. Farmers adopt new practices gradually. Trust accumulates through experience rather than marketing. When different actors reinforce the same systems, adoption accelerates. When they compete for attention, confusion grows.

Changing the Narrative Without Changing the Reality Overnight

The language around African agriculture has begun to evolve. Smallholder farming is increasingly described as agribusiness rather than subsistence. The reframing attracts investors and policymakers, though the lived reality on farms changes more slowly.

Climate pressure ensures that agriculture cannot remain static. Extreme weather events have already altered planting cycles in parts of West and East Africa. Information becomes as valuable as inputs. Decisions once made by intuition now depend on data delivered through basic phones.

What emerges from conversations like this is not a neat technological solution. It is a gradual restructuring of how agriculture connects to finance, information, and policy. Progress appears uneven. Some regions move faster than others. Some tools gain traction while others fade.

The green economy, at least in this context, looks less like a new sector and more like agriculture catching up with systems that other industries adopted years ago. The work remains slow. The stakes remain high. And for now, most of it still begins with a farmer deciding whether the rain will come tomorrow.

Go to TECHTRENDSKE.co.ke for more tech and business news from the African continent and across the world.

Follow us on WhatsApp, Telegram, Twitter, and Facebook, or subscribe to our weekly newsletter to ensure you don’t miss out on any future updates. Send tips to editorial@techtrendsmedia.co.ke