Picking up the Pieces: What’s Next for Zimbabwe’s Economy?

Dustin Homer, Director of Client Solutions, Fraym

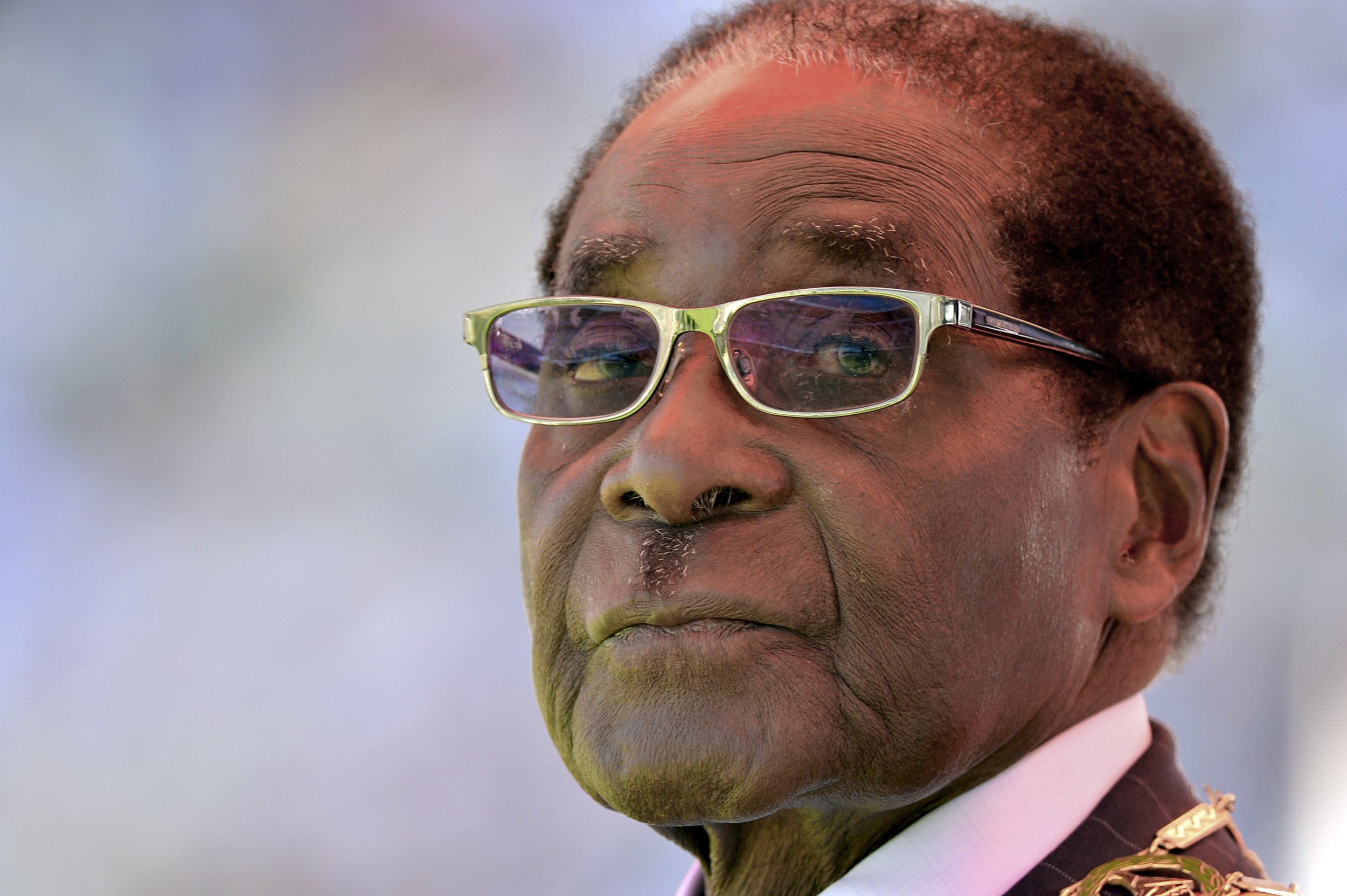

“Bob is gone.” At the end of November 2017, under intense pressure, Robert Mugabe stepped down as president of Zimbabwe – a position the controversial leader had held for 30 years. Global response to the news was cautiously optimistic. Even within the country, celebration was muted. With the transition underway, what will it take to make things better in Zimbabwe? Can the fragile economy of a country once known as the “Bread Basket of Africa” now be revived as one of the continent’s contemporary greats? And how should international investors approach opportunities in Zimbabwe?

There are no simple answers or guaranteed outcomes. And good information on Zimbabwe is hard to come by. But sophisticated data analysis—like the work done by Fraym—can be used to illustrate promising opportunities for commercial ventures and social development. Both have the power to measurably improve the lives of Zimbabweans.

There’s no question that the Zimbabwean economy was decimated during Mugabe’s regime. Record-breaking hyperinflation, high unemployment (only 53% of working-age adults are employed), periodic fuel and food shortages, crippling public debt – officially sitting at USD 11.6 billion (82% of GDP) as of last year – and, most recently, a chronic lack of cash, have all afflicted the country since the early 2000s.

Despite all this, Zimbabwe remains abundant in natural resources. In 2017, meanwhile, Harare ranked 51st on the Fraym Urban Markets Index, a first-time assessment of Africa’s major urban centres. Zimbabwe’s other major urban areas, Bulawayo and Chitungwiza, ranked 121 and 149 respectively on the Index, which analysed 169 populous urban areas across the continent according to three vectors: economic activity, consumer behaviour and economic connectivity. Using a multi-tiered approach, this type of geospatial data analysis provides a more nuanced, accurate and emotionally detached picture for investors—who are so often geographically removed from the markets they’re investigating.

It’s not just about recognizing commercial market potential, though. Data science techniques can also be used to guide Zimbabwe’s social development efforts. For example, the proportion of adults with post-secondary education in the country has doubled over the past decade (currently 17%). How can this be further accelerated? The first step of the process is to specifically identify where to target scarce financial and human resources. In a place like Zimbabwe, many people in poverty-affected communities are hard to reach and difficult to account for in official statistics. Geospatial data analysis tackles that challenge, turning to a combination of satellite imagery, pre-existing data sets and sophisticated algorithms to paint a more precise population picture of these inaccessible areas.

Fraym has constructed models that allow us to understand issues and dynamics such as employment, literacy, child nutrition and mortality, infrastructure and even attitudes to domestic violence. For example, we uncovered that 36% of rural Zimbabwean children stop attending school after or during primary school. We brought together data like this to pinpoint the most vulnerable communities in Zimbabwe. These spotlighted areas, unsurprisingly far away from urban centres, can then be targeted to rectify inequalities in resource access, and encourage economic revival. The African Development Bank is now using a similar technology-driven identification strategy to catalyse activities by companies, governments, and NGOs in the poorest and most vulnerable communities across the continent.

One final point about Zimbabwe is that even in uncertain periods, opportunity exists. For example, the cash shortages of the past few years resulted in a wholesale embrace of digital banking, largely out of necessity. Mobile phone ownership is high in both urban and rural Zimbabwe: 85% of rural Zimbabweans have access to mobile phones in their households, and that rate is as high as 98% in urban Zimbabwe. As already mentioned in another piece, the Ecocash mobile-enabled funds transfer service has become a staple of daily life in Zimbabwe, to the extent that electronic money now accounts for 70% of all payments in the country. Several digital banking services, like Mukuru, have also emerged to cater for the Zimbabwean diaspora sending remittances back home.

Looking at these examples, digital tools are already available for decision-makers in Zimbabwe. Accessed and used optimally, these tools – and the many other technology-driven solutions yet to be explored – can enable economic revival and accelerate social development in a nation with much potential.