Community networks in Kenya most effective in fostering inclusion for people with disabilities

Community networks are the best driving force in bridging the digital divide, particularly achieving digital inclusion, especially for Persons With Disabilities (PWDs).

This is according to the Kenya ICT Network’s (KICTANet) 2024 study report titled ”Best Practices for Digital Inclusion of PWDs in Kenyan Community Networks.”

According to KICTANet, Kenya defines disability as a ‘physical, sensory, memory or other impairment including any visual, hearing, learning or physical incapacity that adversely impacts social, economic, or environmental participation.’

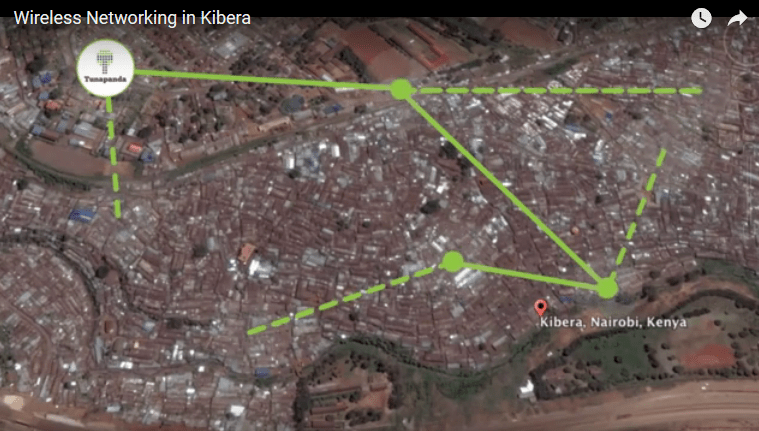

On the other hand, community networks are referred to as decentralised, community-owned and community-operated communication infrastructures that provide accessible, dependable and locally relevant connections.

“These may seem like separate entities, but when they intersect, inclusion and accessibility come in,” KICTANet noted.

“In light of this, the need to bridge the digital divide between community networks and disability is apparent.”

Simply put, the connection between disability and community networks serves as the best way to breed inclusion.

According to the report, unlike the usual top-down approach led by Internet Service Providers (ISP), Community Networks are community-driven.

They allow local stakeholders to actively participate in network design, deployment, operation and maintenance.

This grassroots approach, the report says, is more inclusive and adaptable to the specific needs of the community.

Availability, Affordability and Access

Community Networks are often established to provide connectivity in areas without internet coverage from mainstream internet service providers. They also present a cheaper alternative to the regular Internet rates where telecommunication companies offer connectivity.

The survey notes that in 2023, the affordability of both fixed and mobile broadband services improved globally.

“The cost of a data-only mobile broadband plan decreased from 1.5% to 1.3% of gross national income (GNI) per capita, while fixed-broadband plans dropped from 3.2% to 2.9% of GNI per capita,” the report reads in part.

“Despite this positive trend, affordability remains a significant barrier to internet access, particularly in low-income economies such as Kenya.”

The main challenges include high connection and subscription costs, unreliable connectivity (including regular power blackouts), and inadequate internet infrastructure.

The report further indicates that approximately 16% of the global population, or about 1.3 billion people, have disabilities.

According to Kenya’s 2019 national census, around 900,000 individuals, or 2.2% of the country’s population, have disabilities.

On mobile phone and internet use, the study indicates that PWDs in Kenya are less likely to use mobile phones and mobile internet compared to those without disabilities.

“This exacerbates their social exclusion, especially in the highly digital post-pandemic world.”

“For women with disabilities, this issue is compounded by an intersectional gap, as they are even less likely to use mobile internet than men with disabilities.”

In contrast, the gender gap in mobile internet usage among non-disabled men and women in Kenya is minimal, with usage rates of 92% and 91%, respectively.

“The digital divide in Kenya is significant,” the report continues.

A 2022 report by the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) reveals a stark disparity. Only 11% of persons with disabilities use the internet, compared to 22.9% of the non-disabled population.

Persons with disabilities often face difficult economic choices where they have to prioritise different needs.

In Kenya, there’s a significant gap in mobile internet usage between non-disabled individuals and those with disabilities, with 85% fewer persons with disabilities using mobile internet.

The gap in mobile phone ownership is much smaller, at 11%.

Further, a report by Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) on the barriers to accessing ICTs in Kenya for persons with disabilities listed several challenges, including accessing information, limited access to ICTs and assistive tech, and the lack of appropriate knowledge and skills.

The KICTANet survey notes that community networks in Kenya, which operate in digitally marginalised areas, offer a unique opportunity to address barriers faced by persons with disabilities.

However, the potential of these networks to inclusively and effectively support PWDs is yet to be fully explored.

In Kenya and other African countries, the survey indicates that community networks are often based on existing social structures within the community, relying heavily on local associations, traditional authorities, churches, and other community groups to establish and sustain the network.

“Social cohesion plays a crucial role in maintaining the community’s trust and integrating the network into the community,” the report reads.

It further highlights that community networks have the potential to promote digital inclusion for underserved populations.

This is because they offer affordable internet access in areas neglected by telecommunications companies or where government communication infrastructure deployment is low.

The report by KICTANet in collaboration with CIPESA focuses on the fact that community networks hold the key to ensuring that persons with disabilities are digitally included.

The study examines the accessibility of these community networks against existing policies, laws and regulations, and public programs for persons with disabilities.

“It involved surveys, interviews, and workshops with disability stakeholders to gather firsthand information on digital inclusion within these networks,” KICTANet said.

“This informed and brought to the fore issues affecting persons with disabilities in the digital space, and contributed to the impact-driven recommendations in the report.”

KICTANet further said that the survey also addresses barriers to inclusive practices in the usability of ICTs by people with disabilities.

These barriers include misconceptions about disability needs, outdated traditions, stereotyping, digital illiteracy, limited access to training opportunities due to financial constraints, and technological and infrastructural challenges.

The study report, further, provides detailed insights into different aspects and provisions of legal frameworks and serves as a guidebook for best practices in digital inclusion.

It highlights the significance of involving people with disabilities in decision-making, investing in specialised accessibility features both offline and online, fostering partnerships and collaborations, and advocating for increased government funding and support for digital inclusion initiatives within community networks.

Policy and regulatory landscape

The survey also examines various Kenyan policies and programmes related to digital inclusion, highlighting both their strengths and shortcomings, particularly in relation to PWDs.

The Kenyan Constitution guarantees fundamental rights and freedoms for all individuals, including PWDs and mandates the state to promote social justice and inclusivity.

Article 54 specifically addresses the rights of PWDs, ensuring reasonable access to information and communication.

However, the report further indicates that key legislation like the Kenya Information and Communications Act (KICA) and Disability Act fall short in explicitly addressing digital accessibility.

“The KICA, while establishing the Communications Authority of Kenya (CA) and Universal Service Fund (USF), doesn’t mandate licensees to ensure service accessibility as a licensing requirement,” the survey reads in part.

“The Disability Act, though focused on the rights and rehabilitation of PWDs, needs to be updated to reflect the current digital landscape and address the accessibility of emerging technologies.”

For Vision 2030, Kenya’s long-term development blueprint emphasises social inclusion and aims to make the country globally competitive, however, it needs a more explicit focus on digital inclusion for PWDs across all sectors.

The study shows that even though the National ICT Policy 2019 outlines the government’s ICT strategy it has implementation gaps related to universal access, accessibility, and consumer protection for PWDs.

Equally, the Digital Economy Blueprint recognizes the importance of accessible infrastructure and acknowledges legislative gaps in digital accessibility for PWDs.

However, its definition of disability and its understanding of digital accessibility appear limited.

Under education, the report noted that Kenya’s education system is undergoing reforms to incorporate ICT and promote inclusive education.

The National Pre-Primary Education Policy focuses on inclusive education but lacks specific provisions for assistive technologies and digital tools for learners with disabilities.

On the same length, the Policy on Information and Communication Technology in Education and Training (2021) supports ICT integration for inclusive education but doesn’t adequately address the cost barriers associated with assistive technologies.

“Additionally, the Sector Policy and Implementation Guidelines for Learners and Trainees with Disabilities (2018) promotes inclusive education for various disabilities but needs to be strengthened in the area of digital accessibility,” the report reads.

On National Programs and Initiatives, disability-specific initiatives like the National Development Fund for Persons with Disabilities (NDFPWD) and the National Fund for the Disabled of Kenya (NFDK) provide funding for assistive devices but show limited focus on digital assistive technologies.

“The USF aims to extend ICT access to underserved areas but requires more effective management and targeted efforts to benefit PWDs.”

“The ICT Authority (ICTA) offers digital training programs but most of these programs lack explicit provisions for the inclusion of PWDs and the accessibility of training materials and tools.”

The report suggests that while Kenya’s policy framework acknowledges the importance of digital inclusion, the actual implementation and enforcement of these policies are lagging, especially concerning accessibility for PWDs.

Key findings

Of the 14 registered community networks in Kenya that were contacted, 10 responded to a survey conducted by KICTANet, making up 71% of the replies received.

They included AHERINET, Angaza Community Network, Athi Community Network, Kijiji Yeetu (Siaya), Tanda Community Network, Action Pour Le Progres, Ngikeyokok, Global Innovation Valley (GIV), Oasis Mathare, Dunia Moja, CISS, and Lanet Umoja.

On access to USF, 80.6% had never accessed the fund with 16.1% having access to some extent and 3.2% of the CNs having access.

“This suggests a lack of public awareness, inadequate information reaching the intended beneficiaries, and ineffective targeted communication to community networks,” the report reads.

On application and benefits from the USF, only 3.3% of the respondents who indicated that they had access to USF, had actually applied for or benefited from the fund while 96.7% did not apply for or benefit.

This shows that there is still limited awareness or engagement of community networks with the USF.

On staff training on accessibility ICT features, the report shows that 32.3% of the CN staff possess the necessary skills and knowledge, while 25.8% have received some training, and 41.9% still need training.

“This highlights the importance of training staff members to ensure they can offer necessary accommodations and make projects and activities inclusive and accessible for persons with disabilities,” the report says.

Concerning accessibility of emergency services, 32.3% of the respondents reported that the publicly available emergency communications services within the CNs were accessible to PWDs.

25.8% indicated that they were accessible to some extent while 41.9% mentioned that they do not have accessible emergency services within their CNs.

The survey further shows that there was an indication of improvement in the usability of common platforms to access emergency services compared to the responses on accessibility.

48.4% mentioned that PWDs could use everyday means of communication to access emergency services, while 22.6% indicated that it could be possible to some extent.

In comparison, 29% stated that it was impossible within their community networks.

“Furthermore, 51.6% of the respondents mentioned that their CNs created awareness about using emergency services in accessible formats.”

“Additionally, 19.4% stated that they did this to some extent, while 29% replied that they did not provide such awareness.”

The survey noted that the data on access to emergency services for persons with disabilities indicates a lack of provisions for protecting individuals with disabilities during humanitarian emergencies.

Under on-premises access and equipment and software accessibility, the research further indicates that 38.7% confirmed that their CNs are accessible, while 19.4% reported accessibility to some extent. However, 41.9% of respondents stated that their CNs were inaccessible.

On CN we accessibility, 51.6% reported having at least one website, while 48.4% did not.

On web accessibility guidelines for use by PWDs, of the 51.6% of the respondents who said that their CNs had a website, only 6.9% of the websites claimed to have been developed as per the web accessibility guidelines, 31% had done it to some extent, and surprisingly 62.1% did not consider any web accessibility guidelines.

The study also sought to understand the extent of compliance among CNs with the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG 2.0) under ISO/ IEC 40500:2021.

Here, only 10.3% of the respondents acknowledged conducting systematic assessments of their websites, website infrastructure, and staff expertise.

“ The CN’s online platforms and websites demonstrated low compliance with web accessibility guidelines,” the report continues.

“Only 20.7% were fully compliant, 37.9% partially compliant, and 41.4% noncompliant.”

On the accessibility of electronic documents on CN websites, 48.3% of the respondents’ sites were completely inaccessible, 34.5% said theirs was accessible to some extent, and only 17.2% were fully accessible.

On the other hand, only 17.2% of respondents reported that they regularly update their procurement policies to ensure that website development service contracts comply with accessibility requirements.

“34.5% indicated doing so to some extent, while 48.3% stated that they did not update their procurement policies for this purpose.”

Further, out of the CNs complying with WCAG 2.0 standards, only 20.7% provide accessibility training to their web developers, 13.8% did so to some extent, while 65.5% of them did not offer any accessibility training.

When web developers and persons with disabilities were asked whether they had received guidance on accessibility testing tools and procedures, 57.7% reported not receiving any guidelines.

26.9% of the respondents indicated they received the guidelines to some extent, and only 15.4% were issued with the testing guidelines.

“This suggests a lack of inclusive procedures in accessibility testing and quality assurance of CNs’ digital platforms,” the study reads.

Routine monitoring and publication of reports on the state of website accessibility within CNs were also assessed.

The data shows that 17.2% publish the reports, 27.6% do so to some extent, and 55.2% do not publish at all.

Lastly, only 17.2% of the respondents were fully involved PWDs in user acceptance testing of new/updated CN websites and digital platforms, while 31% only involved them to some extent, and 51.7% did not.

Based on the above statistics, the following were the main barriers that were identified:

- Misconceptions about the needs and capabilities of PWDs hinder efforts to include them in digital spaces.

- There is limited understanding of the diverse needs of PWDs, including those with invisible disabilities.

- Assistive technologies often focus on single disabilities, creating barriers for individuals with multiple disabilities, consequently making access to digital resources difficult for them.

- There are limited training opportunities for PWDs to enable them to contribute to community networks. Technical jargon and language differences also complicate training and engagement.

- Financial constraints limit the establishment and maintenance of accessible networks.

- Geographic and infrastructural challenges in rural areas create physical barriers, hindering PWDs’ access to community networks.

- Frequent electricity blackouts disrupt operations, affecting PWDs reliant on electrically powered assistive technologies, and thus increase operational costs.

- There is uncertainty about insurance coverage for PWDs working as technical experts in community networks.

- Free and open-source software have limitations, while proprietary alternatives are costly.

- Poor enforcement of accessibility standards and specific regulatory frameworks.

Recommendations

Digital inclusion of PWDs is a continuous process that necessitates cooperation, fairness and dedication to addressing varied needs.

The survey highlighted recommendations that aim to foster an inclusive digital environment for PWDs through a link formed through Community Networks (CN) in order to meet increasing accessibility needs.

For Community Networks, the survey recommended;

- Recognising and investing in specialised accessibility features tailored to the unique needs of PWDs.

- Ensuring active inclusion of PWDs in decision-making processes to genuinely address their needs in the development of community networks.

- Creating accessible documentation in local languages

- Partnering with disability rights groups to increase the involvement of PWDs in the design, development, and implementation of their infrastructure.

- Raising awareness about the importance of accessible community networks for all PWDs and investing and developing the necessary digital infrastructure to support accessibility, particularly in remote areas.

- Establishing baseline software and hardware development standards to ensure all PWDs can utilise community networks.

- Conducting regular ICT gap analyses to identify and address specific challenges hindering PWDs from effectively using community networks near them.

- Adopting open-source or low-cost assistive technologies to improve digital accessibility for a wider spectrum of disabilities.

- Extending digital inclusion practices to other members of A community to facilitate the smooth integration of PWDs into socio-economic activities.

- Collaborating closely with government agencies and other stakeholders providing internet services to promote accessibility for persons with disabilities.

For the government, the report suggested;

- Establishing centres dedicated to designing and developing low-cost or free assistive technologies for people with disabilities. The government should significantly increase subsidies to make these technologies more affordable and provide strong incentives to organisations that develop accessibility tools and programs.

- Engaging in open dialogue and collaboration with advocacy groups, PWDs, and digital content developers to develop a supportive legal framework for digital accessibility that considers diverse stakeholder perspectives.

- Supporting ICT resource centres to provide low-cost or free technical assistance on ICT accessibility.

- Supporting community outreach programs such as educational campaigns to highlight the importance of PWDs’ contributions to the digital economy and inform communities about available resources for digital accessibility.

- Intensifying their efforts to adopt international standards and best practices on accessibility to make their digital platforms, including e-government services, accessible to persons with disabilities.

- Encouraging digital content creators and website owners to prioritise accessibility and transparency by publishing audit scores.

- Introducing the Kenya Sign Language into the education curriculum to bridge the communication barrier with persons with hearing disabilities.

- Utilising USF to fund the development of community networks that are easily accessible to persons with disabilities.

For other stakeholder groups, the study recommended;

- Media portraying PWDs fairly and accurately in TV shows, movies, and advertisements. Too often, the content focuses on their limitations, negative portrayal contributes to their exclusion from society, particularly in the digital world.

- Civil society creating platforms for PWDs to share their experiences and perspectives, especially in the digital space.

Follow us on Telegram, Twitter, and Facebook, or subscribe to our weekly newsletter to ensure you don’t miss out on any future updates. Send tips to editorial@techtrendsmedia.co.ke